Kay Coutin writes: The foundations of this church were laid over 900 years ago, when a Norman baron ordered it to be built and provided land to support it in about 1090. Ralph de Chesne, whose name survives in Horsted Keynes, gave the advowson (ie the right to appoint clergy) to the Priory of St Pancras in Lewes.

The appearance of the church has changed considerably in the course of nine centuries. A walk around the outside gives a rough idea of how the building evolved from the original small rectangular plan with an apse, or square East End. In the North wall, which shows alterations, there are six different windows and a door. At the East end the ground falls steeply away.

On the South side stands the Chapel with the aisle extending the length of the Nave. On the window jambs beside the porch are two mass dials which have lost their gnomens or pointers and are now eroded by time and weather. As simple sundials they indicated the time for services before a clock was installed.

Materials.

Stone from the building came from close by. The sandstone has weathered to a pleasing variety of colours revealing the presence of iron which was extracted in this area from pre- Roman times onwards. Horsham stone has been the main roof covering, but except for a few courses over the south aisle, clay tiles are now in place. In the 18th Century wooden shingles which had been used for cladding the south wall were removed to help repair the spire. In 1959 Canadian red cedar was used to reshingle the spire.

Inside the Church.

Entering by the door, clearly dated March 31 1626 in iron nails, the visitor should cross over to the corner beneath the old clockworks. This is the oldest part of the building where the stones were laid 900 years ago.

At first sight one might feel that the interior lacks the aesthetic appeal of a church built entirely at one period but here each feature tells us not only about its development over the years, but also about the ideas and circumstances which led to these changes.

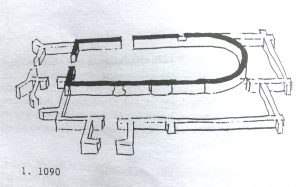

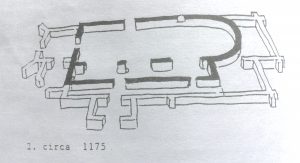

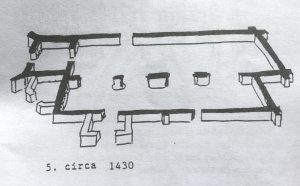

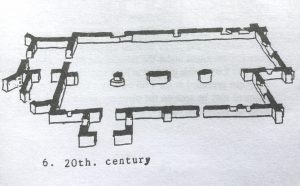

The first structure reached to the small wall projection near the pulpit and in width extended to the half pillar by the tower door. After about a hundred years, at the end of the 12th century, the south wall was altered to allow a narrow lean to aisle to be added. The massive, distinctly Norman, short round pillars replace the existing wall. The new plan allowed for processions, then part of the liturgy. (The dark walls shown in the groundplans show the building as it develops against the context of the existing church building (in fainter lines) in 2017)

The first structure reached to the small wall projection near the pulpit and in width extended to the half pillar by the tower door. After about a hundred years, at the end of the 12th century, the south wall was altered to allow a narrow lean to aisle to be added. The massive, distinctly Norman, short round pillars replace the existing wall. The new plan allowed for processions, then part of the liturgy. (The dark walls shown in the groundplans show the building as it develops against the context of the existing church building (in fainter lines) in 2017)

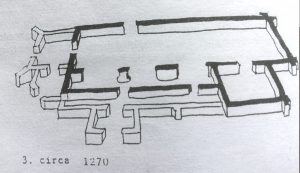

In about 1200 the Chancel was extended to roughly the position of the present Communion rail. It was lit by the lancet window now visible only from outside. In the mid 13th century the chancel was again enlarged, making it as long as the nave, and so taking the East end up to the old boundary of the Churchyard. This was a period of prosperity and increasing population, with more clergy serving the parishes. Light was needed for following the services, which were becoming more elaborate. However a rural church such as this might still only have had one copy of one of the Gospels and a service book.

In about 1200 the Chancel was extended to roughly the position of the present Communion rail. It was lit by the lancet window now visible only from outside. In the mid 13th century the chancel was again enlarged, making it as long as the nave, and so taking the East end up to the old boundary of the Churchyard. This was a period of prosperity and increasing population, with more clergy serving the parishes. Light was needed for following the services, which were becoming more elaborate. However a rural church such as this might still only have had one copy of one of the Gospels and a service book.

The lancet window to the left of the altar is an example of plate tracery: there is no carving on the stone which is flat (ie plat as in french) an early form. The elegant pilasters and capitals emphasise the importance of the chancel.

The decoration on the window splays are part of the 19th Century restoration and replace what remained of the more delicate original work, faint signs of which can be detected beside the blocked window opposite. The walls were probably painted in a similar fashion. Murals found beneath the limewash were too fragmentary to be restored.

To the right of the altar is a trefoil headed piscina for washing the Communion vessels. The drain allowed the consecrated water to return directly to the earth. Of the three seats or sedilla, the wider one was for the priest presiding at the service.

The Chapel (latterly incorporated into the South aisle)

This was built in about 1270 and dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. Another altar was needed if there were more clergy in residence, each of whom would celebrate Mass. A way through to the chapel was made by taking down the wall of the chancel (in the process mutilating the window, which was blocked up) and setting up the fine octagonal pillars, whose form contrasts with the earlier ones at the west end of the Nave.

This was built in about 1270 and dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. Another altar was needed if there were more clergy in residence, each of whom would celebrate Mass. A way through to the chapel was made by taking down the wall of the chancel (in the process mutilating the window, which was blocked up) and setting up the fine octagonal pillars, whose form contrasts with the earlier ones at the west end of the Nave.

The altar was removed after the Reformation in the 16th century, but in Queen Mary’s reign, in 1555, a parishioner, John Bryan, left money in his will, declaring “also I bequeathe for making the altare in Lady Quire viij d”. But as far as we know, it was not until another 400 years had passed that Bryan’s hopes were realised when the present altar was consecrated as a war memorial, with the inscription carved in fine Roman lettering.

The stone frame of the small door in the south wall may have been moved here from the Chancel when the chapel was built. The clergy used it to enter the church without passing through the Nave. The wooden door has recently been replaced by a faithful replica of its predecessor, which was of 17th Century date.

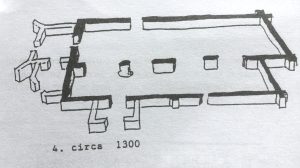

The South Aisle. The chapel reached to the point where the wall recedes beside the arch. Soon after it was completed the narrow aisle of the Norman church was rebuilt to make the full aisle we see today.

The South Aisle. The chapel reached to the point where the wall recedes beside the arch. Soon after it was completed the narrow aisle of the Norman church was rebuilt to make the full aisle we see today.

The Chancel and the Chapel used to be separated entirely from the nave and aisle by a carved wooden screen, the rebate for which can be found close to the floor on each side of the aisle.

The small doorway at the upper level, rediscovered in 1870, gave access through the 12th century wall to the narrow loft of the Rood Screen. Here stood the figures of Christ on the Cross (or Rood), the Virgin Mary and St John. Sometimes sermons were preached from here “in the vulgar tongue” rather than in Latin, and singers performed.

Until Henry VIII’s breach with Rome the laity had remained in the nave, with only the clergy entering the Chancel. Fragments of the screen were found under the floor of the Manor House (built in 1627) so it is possibly that part at least survived in situ until Puritan influence prevailed in the 17th century. Traces or red and green pigment may be seen on the piece preserved in the Priest House museum across the road.

The last major addition was the Tower. It was probably put up in the first half of the 15th century after the Priory’s administration had recovered from a period of decline. The tower which has integral buttresses has a shingled broach spire. In 1426 the parishioners complained about general neglect, so it may be that the tower and the medieval houses along the street (The Priest House, The Cat Inn and the old house replaced by the Manor House) were part of a renewal building programme by the Priory after this date.

The last major addition was the Tower. It was probably put up in the first half of the 15th century after the Priory’s administration had recovered from a period of decline. The tower which has integral buttresses has a shingled broach spire. In 1426 the parishioners complained about general neglect, so it may be that the tower and the medieval houses along the street (The Priest House, The Cat Inn and the old house replaced by the Manor House) were part of a renewal building programme by the Priory after this date.

The tower has pointed ogee headed windows of the period: others, which probably come from elsewhere in the Church, were inserted later when change ringing became popular in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Roof Structure.

The form of this is significant for establishing dates of construction. The oldest section of roof surviving is in the Chapel, where the heavy oak timbers make an A shaped frame, dating from the 13th century. There are no longitudinal members; the stone gable ends give stability. The aisle has a similar roof and is therefore not much later than the Chapel.

The Nave and Chancel probably had the same simple type roof initially but being older would have needed repair, especially the Nave, the earliest part. This part has a crown post roof, the standard form in South East England by the 15th Century. It may well have been constructed when workmen were putting up the tower.

The Chancel roof was replaced in the course of the extensive restoration carried out in the 1860s by Slater and Carpenter. Oak of sufficient length to span the chance was then hard to come by which may account for this ingenious pseudo-hammerbeam design in pine.

Alterations to the Interior.

Great changes were made following the Protestant Reformation of the mid 16th Century. The Priory at Lewes was dissolved in 1537. The Rectory of the Manor and the advowson of St Margaret’s was then granted to Thomas Cromwell by Henry VIII. Later it passed to Anne of Cleves before reverting to the crown, which still holds the advowson. The land previously let out by the Priory became the property of local people.

Royal edicts decreed the removal of the figures on the Rood Screen, Wall decorations were plastered over, while the altar was to be a plain table which could be moved into the nave during the week. Each church was to have a copy of the Bible in English and now there was also the English Prayer Book devised by Archbishop Cranmer, who was later burnt to death during the reign of Queen Mary. In the same year Anne Tree of this parish suffered a similar fate in East Grinstead. There is a modern memorial to her in the South Aisle.

The intensity of Protestant feeling saw the destruction of the altar in the Lady Quire and the breaking of the holy water stoup. The North door was blocked up when festivals and processions were banned.

The Restoration of Charles II in 1660 brought a return to ceremony, wearing of vestments and rails to protect the altar in the Sanctuary. A gallery was built at the West End. In those days musicians and choir stood at the end of the nave. A barrel organ was in use in 1835 but had only a few tunes and was replaced by a harmonium and eventually an organ. The present organ was built by WM Hill and Son and installed for Easter 1899. It has two keyboards and eight sets of sounding pipes. It was completely overhauled on its centenary.

The Victorian Restoration of the 1860s.

The next major rearrangement left the interior much as we see it today. A new pulpit, choir stalls, pews, stained glass windows, a new vestry, the chancel roof rebuilt, repairs to the nave roof and the porch remade. The “mean gallery” was removed and an organ loft put up. The pews had to be removed after an infestation by woodworm and the choir stalls were removed in the early 21st century.

The next major rearrangement left the interior much as we see it today. A new pulpit, choir stalls, pews, stained glass windows, a new vestry, the chancel roof rebuilt, repairs to the nave roof and the porch remade. The “mean gallery” was removed and an organ loft put up. The pews had to be removed after an infestation by woodworm and the choir stalls were removed in the early 21st century.